All The Lives We Cannot Live

On happiness, choice, and the liberating meaninglessness of our finite lives

It isn’t the thing you do, dear,

It’s the thing you leave undone

That gives you a bit of a heartache

At the setting of the sun.

The tender word forgotten;

The letter you did not write;

The flowers you did not send, dear,

Are your haunting ghosts at night.

—Margaret E. Sangster, The Sin Of Omission

One can spend years—even the whole of life—searching for purpose and meaning and happiness in this world, not realizing the more he tries to catch them the more they elude him. What makes matters worse is our time is finite and the end is unpredictable.

Here’s a liberating truth, Oliver Burkeman writes in his book Four Thousand Weeks: “what you do with your life doesn’t matter all that much—and when it comes to how you’re using your finite time, the universe absolutely could not care less.” He continues:

“In other words, you almost certainly won’t put a dent in the universe.

[…]

Cosmic insignificance therapy is an invitation to face the truth about your irrelevance in the grand scheme of things. To embrace it, to whatever extent you can.”

There is a certain sense of relief—even joy—in the realization that nothing we ever do will really matter in the grand scheme of things. The universe itself will keep going until everything ceases to exist. For me, everything will cease to exist when I do.

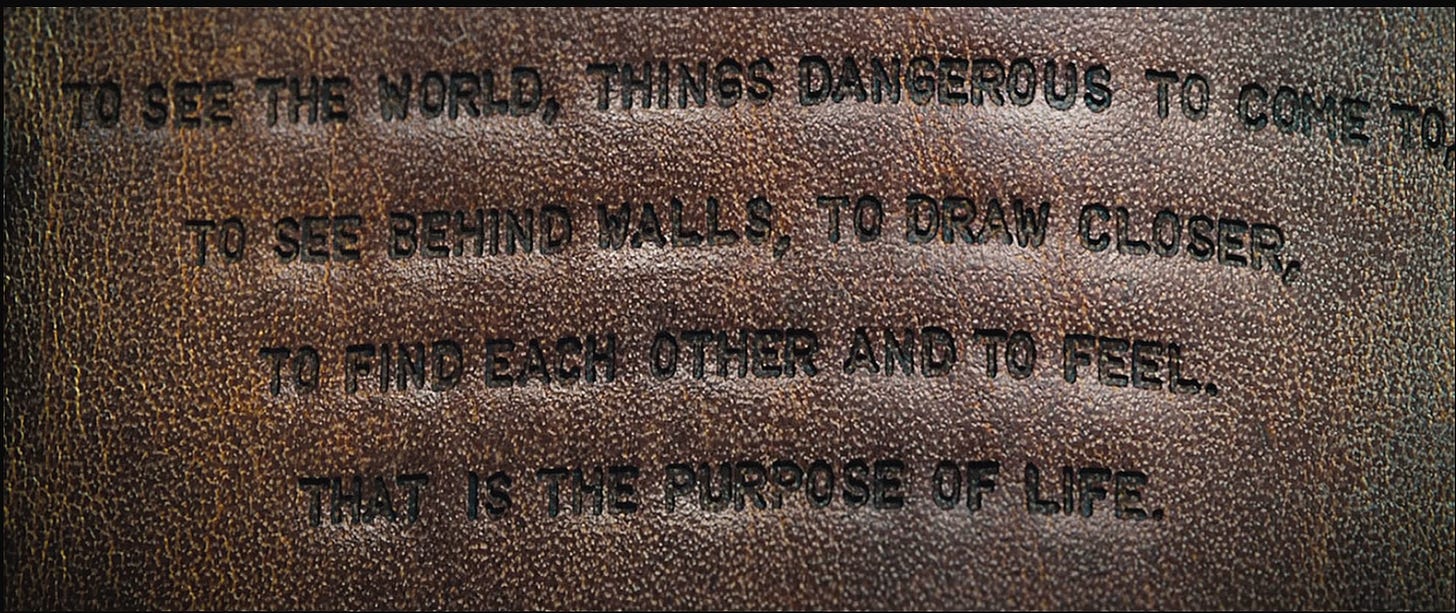

This is not an invitation to nihilism but instead to consideration of what matters: that we are here because we are here. “We,” not “I.” We exist in a world where invisible threads connect us all—threads stretching across time such that we find ourselves connected to everyone that came before us, their actions still vibrating across time making us merely the current chapter in the book of the history of the universe. It does not matter to the universe what we do but it matters, to whatever extent, what we do to and with other people. What some individuals did in the past—Napolean, Cleopatra, Kepler, Galileo, Aristotle, Einstein, Jane Austen, Marie Curie, Van Gogh, Da Vinci, Emily Dickinson—impacts us even today. But even the people that we don’t remember, the ones who didn’t leave an indelible mark on human history, mattered to the ones around them and us in ways we can’t imagine.

James Baldwin once wrote, “I think all of our voyages drive us there; for I have always felt that a human being could only be saved by another human being. I am aware that we do not save each other very often. But I am also aware that we save each other some of the time.”

What we do matters in the sense that our actions are a vote in favor of what kind of world we want to create now that we find ourselves living in one. The infinite choices we face within our finite time force us to search for the right way to live. We find ourselves asking for meaning and purpose, perpetually in the pursuit of happiness.

But the reality is that there is nothing we can do or achieve that will make us happy. There is no becoming happy, there is only being happy.

Viktor Frankl, a psychiatrist who survived the horrors of concentration camps, losing his family to those same horrors, wrote in his book Yes To Life: In Spite of Everything, a collection of lectures he gave in 1946:

“The fact, and only the fact, that we are mortal, that our lives are finite, that our time is restricted and our possibilities are limited, this fact is what makes it meaningful to do something, to exploit a possibility and make it become a reality, to fulfill it, to use our time and occupy it. Death gives us a compulsion to do so. Therefore, death forms the background against which our act of being becomes a responsibility.”

One can’t become happy, as if it’s a destination to reach, one can only ever be happy. Oliver Burkeman writes, echoing a central insight from the ancient Chinese religion of Taoism, “The wise man is like a tree that bends instead of breaking in the wind, or water that flows around obstacles in its path. Things just are the way they are, such metaphors suggest, no matter how vigorously you might wish they weren’t—and your only hope of exercising any real influence over the world is to work with that fact, instead of against it.”

Carl Jung, advising someone on how to live life, wrote in a letter, “the individual path is the way you make for yourself, which is never prescribed, which you do not know in advance, and which simply comes into being itself when you put one foot in front of the other.” All one can do is the next right thing, whatever that may be in that moment, and each individual has to create his own path. A sentiment echoed by the 13th-century poet Rumi, “When setting out on a journey, do not seek advice from those who have never left home.”

“There are infinitely many kinds of beautiful lives,” writes Maria Popova in her book Figuring. “How, in this blink of existence bookended by nothingness, do we attain completeness of being?”

James Hollis, a Jungian analyst in conversation with Oliver Burkeman warns against living a life devoid of meaning—whatever meaning is to you:

“If you’re not living a purposeful life or a life that you find meaningful, then for heaven’s sake, change it—for the simple reason that you’re not here forever. Don’t put off until retirement to go back and pick up the pieces of your life you left behind, because you may not reach retirement, or you may find yourself dealing with physical infirmity and so forth.”

The same finitude of our lives that scares and worries us is what gives anything meaning, forcing upon us a sense of urgency without which we would find ourselves in a state of intellectual—even physical—slumber forever. Meaning, much like happiness, cannot be found but can only be created. Each of us—within the context of our limitations and our moment in time and place—has to define our own meaning and purpose.

“Any finite life—even the best one you could possibly imagine—is therefore a matter of ceaselessly waving goodbye to possibility. The only real question about all this finitude is whether we're willing to confront it or not."—Oliver Burkeman, Four Thousand Weeks

How should we like it were stars to burn

With a passion for us we could not return?

If equal affection cannot be,

Let the more loving one be me.

—W. H. Auden

Another wonderful post. So much to think about!

Reading this was such a delight. Are you by any chance reading All the Light We Cannot See?