Benjamín Labatut's fiction and the insanity of scientific rationality

On Benjamín Labatut’s The MANIAC, his thoughts on writing and fiction, and humanity tiktok-ing its way to annihilation

In this essay: the myth of Prometheus and Pandora → Benjamín Labatut’s book The MANIAC, a fictional biography → Labatut’s life and his thoughts on fiction and writing → John von Neumann, genius, and madness of scientific endeavors → AlphaGo defeating the world Go champion and some thoughts on artificial intelligence as envisioned by John von Neumann.

Prometheus and Pandora

Zeus charged two brothers—Prometheus and Epimetheus—with the task of populating the world with humans.

Prometheus created the first humans—men. Wanting them to be warm on a cold rock, against Zeus’s warnings, Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to men. Enraged, Zeus punished Prometheus by chaining him to a rock for eternity where he would be attacked by a huge eagle every day.

But Zeus didn’t stop there. He ordered Hephaestus to mold the first woman—Pandora—and demanded that she be perpetually curious about all things.

Epimetheus fell in love with Pandora and they got married. With Zeus’s permission, they lived on Earth. Perhaps as a parting gift, Zeus gave Pandora a box and told her never to open it. But curiosity was in Pandora’s nature, so one day she opened the box, and cruelty, hatred, and despair escaped into the world until she slammed the box shut. Only one thing remained under the lid of that box—hope.

In a world of men who wielded the fire of the gods, in a world filled with evil and despair, one must wonder why hope remained locked in Pandora’s box. Did it give the only woman on Earth the power to save man from himself by releasing hope in their darkest hour? I like to think so. After all, we live in a world made by men driven to madness in pursuit of rationality.

We killed God and replaced him with reason

Benjamín Labatut, the writer of The MANIAC and When We Cease To Understand The World, told Sam Leith in an interview for The Guardian, “Dreaming of a secular paradise we killed God and replaced him with reason—but humankind is never gonna rid itself of its impulse towards apotheosis; we’re driven by this thirst for the absolute that’s cooked into our minds. Every nymph and every god we slayed brought us more power…and more despair. It just cast a bigger darkness on the world. You turn your eyes towards the light and you’re blinded: by AI, by tech, by going to the stars. And you turn around and you see the sort of Lovecraftian demons that are welling up from within us.”

In Labatut’s book The MANIAC, Eugene Wigner says of John von Neumann, “It is not the particularly perverse destructiveness of one specific invention that creates danger. The danger is intrinsic. For progress, there is no cure.”

“You cannot step outside of the paradise and then step back in,” Labatut told the actress Natalie Portman when she interviewed him on her Instagram for her book club. The fire cannot be returned, and neither can hatred, despair, and cruelty. The path of technological progress we have been on in the past century—and this one—is fraught with dangers of our own making, spearheaded by a few men of unmatched genius, men that seem like aliens walking among us mortals, men like John von Neumann—maniacs on their quest to create a world of their imagination, no matter the personal cost.

This is the story Benjamín Labatut’s The MANIAC tells—a tale of three men, maniacs in their own ways, rebuilding our reality.

Labatut’s fiction, facts, and the blurry line in-between

In her New Yorker review of When We Cease To Understand The World, Ruth Franklin writes, "Is it responsible for a fiction writer, or a writer of history, to pay so little attention to the line between the two?”

The two she refers to are the facts and the fiction in Labatut’s stories. The MANIAC, just like his previous book, is based on real characters and their real stories. It is 95% facts, as Labatut would say. But the rest 5% is fiction, and that blurry—often impossible to detect—line is what Franklin calls questionable, nightmarish even.

Labatut takes the story of John von Neumann and skillfully distorts his biography, blending fact and fiction, to convey the darkness at the heart of the story.

In his interview with Sam Leith, Labatut said, "I’m not a serious thinker. I’m a writer: that’s very different. I think a writer’s intelligence has to be alive, has to be incomplete. It has to carry contradiction. It has to be sort of haphazard and amateur.”

The shape of stories

In writing The MANIAC, Labatut lets the research guide the structure, voices, and perspectives. He tries to include as little fiction as possible. Research guides the tone of the story—a found material sort of approach. In his interview with Adam Dalva for Literary Hub, he talks about walking around listening to the people in his book for a couple of years. In the book, he writes about von Neumann’s daughter carrying a piece of graph paper in her pocket. When Adam Dalva reached out to Marina von Neumann Whitman—von Neumann’s daughter—to ask her about it, she found it uncanny that Labatut knew such specific details about her life.

“I don’t worry much about the shapes of the stories; it is all about research; I try to find things. To me, finding some other person’s phrase is more important than coming up with it myself. It is the part that I enjoy. In that sense, writing has become more akin to walking and picking stuff above the ground,” said Labatut in an interview with the Louisiana Channel.

“I get as close as I can to reality, and then step back. What are the stranger meanings that are coming through? What things didn’t happen but should’ve happened? I’m doing an exercise in apocryphalism,” Labatut told Adam Dalva.

"While I am researching it, it will determine many things. I am not just looking for data, I am looking for the shape of the story, and that's got to do with what is available. For example, in certain texts, there are scraps of information, lesser-known characters, and people who left no mark on history. Then I must create fiction around it, but the heart of the story is something that comes out of the research. So, to me, it is more akin to looking at the world than to thinking about it," he says.

To Labatut, writing and fiction are sacred endeavors. He isn’t a fan of the novel as a form, he doesn’t care much for self-expression. To him, writing is a much more sacred thing. Fiction is a human tool, he says, that we developed to give reality a human shape, to construct meaning, and to understand what is presented to us. Fiction is not something writers do but are just professionals at it. Many writers have lost their connection to it, according to Labatut.

“Meaning isn’t something inherently present in the world but is something that comes from us. Stories help us look at once at the outside world and at our deranged internal landscape.”—Benjamín Labatut

Labatut is interested in exploring realms beyond self-expression. He wants to write about things that can’t be written about. He is interested in genius, in melding literature and science, to construct a new perspective of our reality.

Literature and science

In an interview, he said, “Literature and science are two of the ways in which we build our sense of the world. Literature is like an older crazy sister of science because it is disorganized. It is not tied down to any set of ideas of the truth so that it can consider anything, and in that sense, it has a freedom that science can’t aspire to. I think of literature as a science that really cares about experiments, you can consider the wildest ideas, and you can play with theories that are wrong, that are delirious and insane.”

He goes on: “Literature has no power at all, and because of that, it is very precious because we can play with ideas that contradict self-evident meanings in the world, and that is a great source of beauty and inspiration. It is a great source of fun, too…You are never just looking at a flower. You look at a flower and have an emotional tone and are contaminated by your other senses, memories biting at you. It is very hard to give any measure about what it feels like to be alive from moment to moment. It is not realism. Our experience of the world is not realistic at all. It is hallucinatory. That is kind of what literature should mirror.”

But what is it that he is trying to do with his fiction? What moves him to explore and write about something?

“We live in a world that is bigger than us. It can be terrifying, but it is also inspiring. We cannot survive without mysteries. Mysteries are more important than truth. Writing should give access to the world and at the same time darken it for you so that it becomes mysterious again.”

“You should be moved by what you are investigating. You should be moved by the world and transmit that. That feeling you get when you perceive or bump into something hard to believe or so beautiful that it is hard to put into words. Fascination lies at the root of everything that I try to do. The world is becoming so that it is very hard to feel fascinated. We are dulled down.“

In his review for The New York Times, Tom McCarthy wonders why not simply write a book of non-fiction. What does MANIAC and the writer behind it gain by shrouding the facts in the guise of fiction?

Finally, realizing it doesn’t really matter, McCarthy writes, “At its best, as in the stunning opening sequence reconstructing the murder-suicide of the physicist Paul Ehrenfest and his disabled son, or in the final section’s gripping account of a computer defeating the world’s best human Go player, you just throw your hands up and think, Who cares what discourse label we assign to this stuff? It’s great.”

Even Ruth Franklin had to concede. While reading When We Cease To Understand The World, at a certain point, she stopped compulsively Googling the facts, simply allowing the story—Labatut’s fiction—to flow and take over.

The MAD Science

“…von Neumann had mathematically demonstrated that there is always a rational course of action for two-player games, provided (and herein lies the catch) that their interests are diametrically opposed.”—excerpt from The MANIAC, Oskar Morgenstern talking about the concept of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) in game theory he co-founded with John von Neumann.

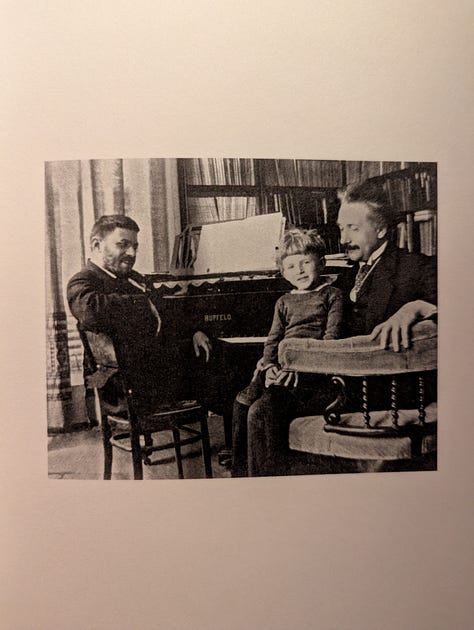

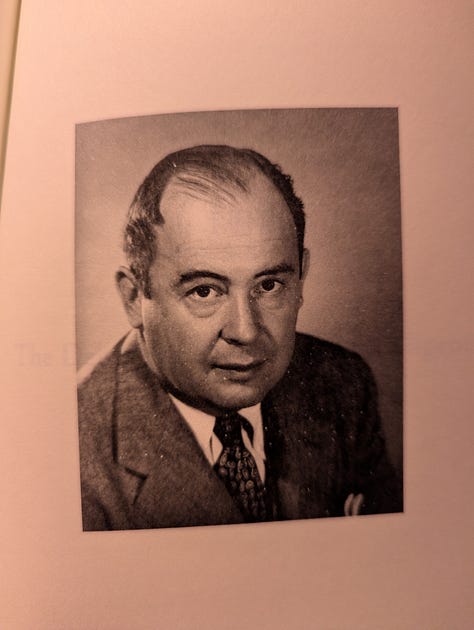

The MANIAC opens with a short narrative about an Austrian physicist, Paul Ehrenfest, a friend of Einstein, living in the Netherlands during an uncertain time in the early 1930s. It has no connection to the story of John von Neumann other than the utter irrationality of logic and the fine line between reason and madness.

In 1933, Ehrenfest, afraid of the consequences of the rise of the Nazis in Germany, traveled to the institution for children with Down syndrome where his 15-year-old son lived and killed him. The harrowing sequence ends with Ehrenfest killing himself.

In his review of The MANIAC for The Atlantic, Adam Kirsch wrote, “In Labatut’s telling, Ehrenfest’s act was a premonition not just of Nazi crimes, but of the terrifying development of modern science. He could think of no better way to keep his son ‘safe from the strange new rationality that was beginning to take shape all round them, a profoundly inhuman form of intelligence that was completely indifferent to mankind’s deepest needs.’”

The majority of The MANIAC takes us through the life of the Hungarian-born polymath John (János) von Neumann—the smartest man who ever lived. Hans Bethe—winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1967—once said of von Neumann, “I have sometimes wondered whether a brain like von Neumann’s does not indicate a species superior to that of man.”

An alien among us

János von Neumann was an alien among Prometheus’s mortal men. In the book, we never see his own perspective, but instead see his life and his impact on the world through the lens of others around him: friends, family, enemies, and admirers.

“A single narrator has too much authority…Monsters and gods should not be given a voice,” Labatut said in an interview with Adam Dalva when asked about why he didn’t provide von Neumann’s perspective.

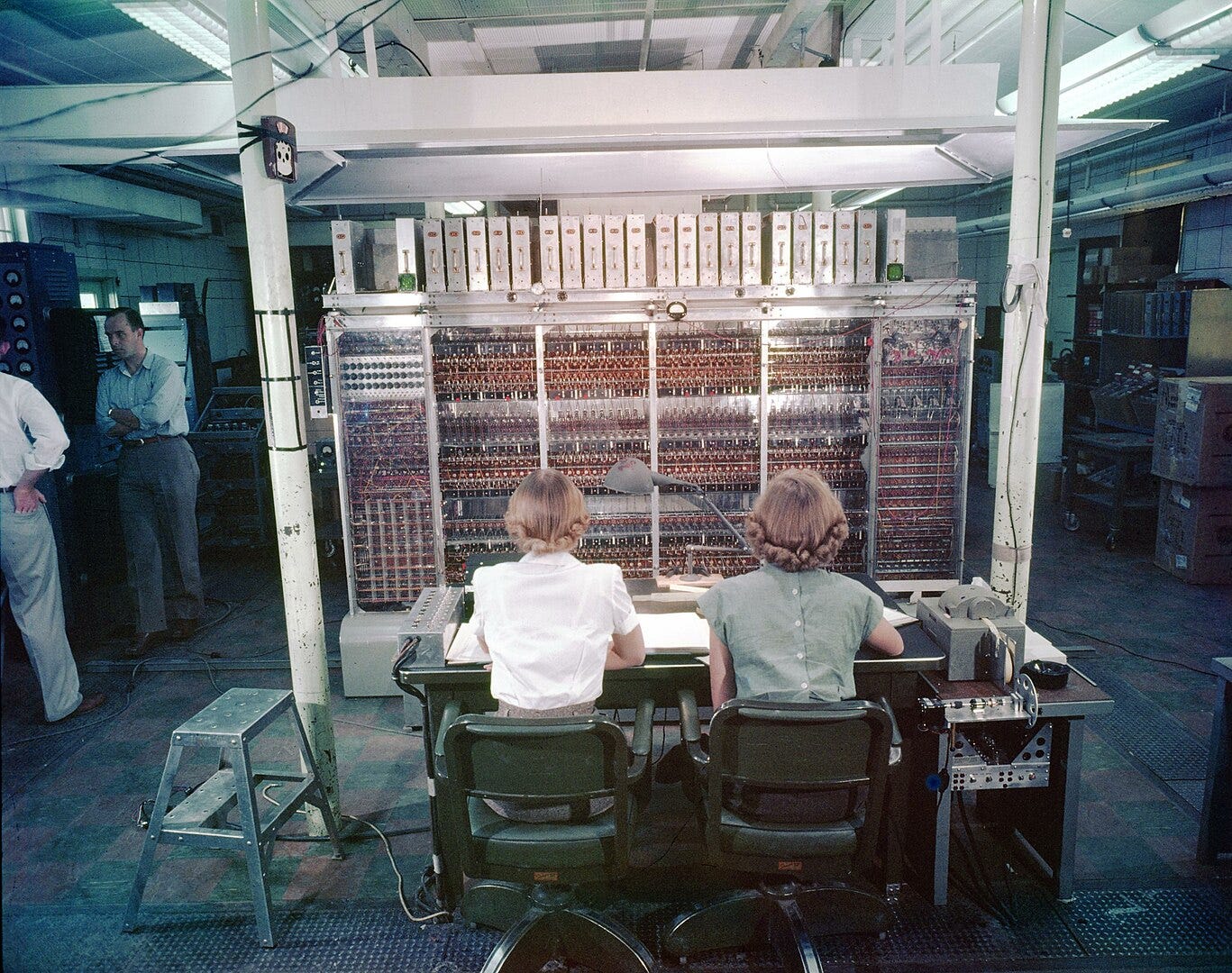

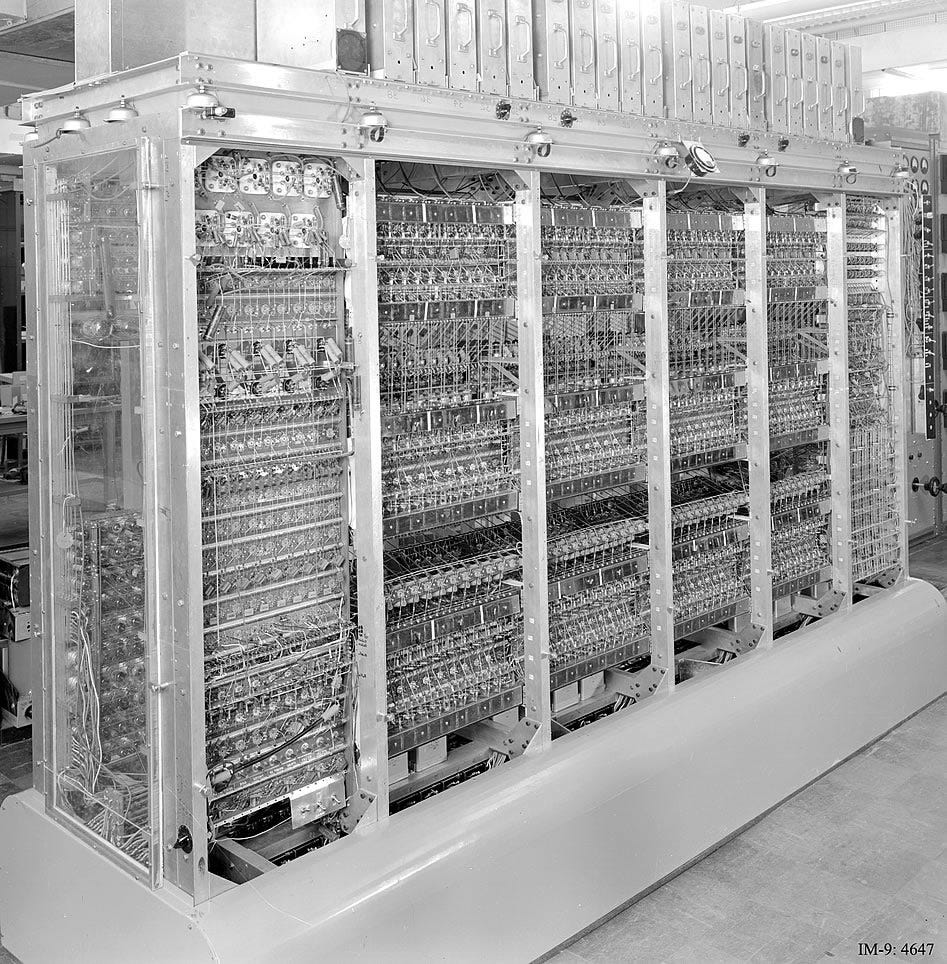

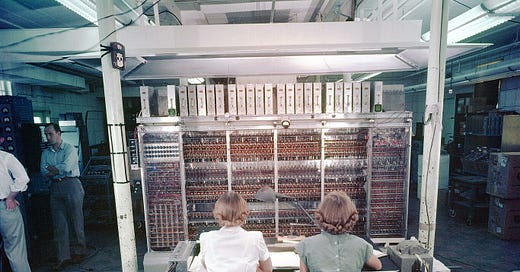

John von Neumann was born in Budapest in 1903, emigrating to the US in 1930 driven by fear of the same enemy as Ehrenfest. He consulted on the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos that led to the apocalyptic mushroom clouds in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He was a pioneer in mathematics, quantum physics, game theory, cellular automata, digital computers, and many more domains. The first computer in Los Alamos National Laboratory in 1952 was based on the von Neumann architecture; the computer was called the MANIAC: Mathematical Analyzer, Numerical Integrator, and Computer. The full name was devised later to fit the acronym, and the acronym was devised to fit the man. The two MANIACs—the man and the machine—played a crucial role in the creation of the Hydrogen Bomb.

“We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried, most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita: Vishnu is trying to persuade the prince that he should do his duty, and to impress him takes on his multiarmed form and says, ‘Now I am become death, the Destroyer of Worlds.’ I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.”—J. Robert Oppenheimer

John von Neumann died in 1957. Cancer, they said, possibly due to radiation exposure at Los Alamos. By then, he had been one of the American government’s most valued advisers on nuclear weapons and strategy, his name forever chained to the machine and the ideas he created.

In his Atlantic review, Adam Kirsch writes, “Even as the novel trains its focus on von Neumann, however, its structure keeps him at a distance; he is not a person we come to know so much as a problem we need to solve. The problem, all of the narrators agree, is that his genius was exhilarating and frightening in equal measure. ‘What he could do. It was so rare and beautiful that to watch him was to weep,’ his math tutor says. ‘Yes, I saw that, but I also saw something else. A sinister, machinelike intelligence that lacked the restraints that bind the rest of us.’”

Mad dreams of reason

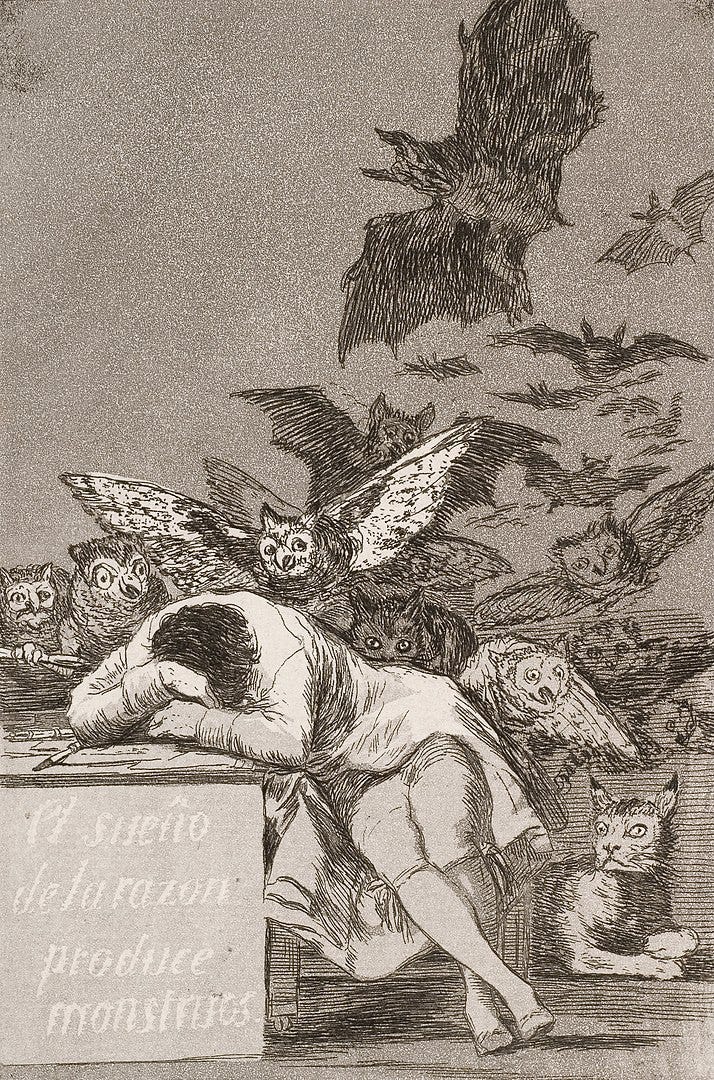

Talking about a painting by Francisco Goya, Ruth Franklin in her New Yorker review points to the phrase: “The sleep of reason produces monsters.”

She contemplates the true meaning of this phrase, “The picture is often taken as Goya’s assertion of faith in Enlightenment values, in the ability of logical thought and empirical observation to sweep away the darkness of superstition. But there is a catch: sueño, the Spanish word for ‘sleep,’ can also be translated as ‘dream.’ What if the monsters are present not because reason isn’t awake to fend them off but because reason, in its slumber, actively generates them? If monsters can exist not despite reason but as a consequence of it, then perhaps we’re not as safe in the rational world—the land of logic and science—as we thought.”

In his book When We Cease To Understand The World, Labatut talks about a chemist in 1782 who mixed Prussian blue with sulphuric acid to produce the poison hydrogen cyanide which, in the formulation known as Zyklon B, led its residue on the bricks of Auschwitz, “coating them with that same brilliant shade of blue.”

The world of logic and science, inhabited by geniuses perpetually in the discovery of the universe’s secrets, has led to a world hellbent on destroying itself. There is an all-consuming ever-present tension in the world between madness and rationality that keeps the machine running: Mutually Assured Destruction.

“We were all little children with respect to the situation which had developed, namely, that we suddenly were dealing with something with which one could blow up the world.”—John von Neumann

In his New York Times review, Tom McCarthy writes about the relationship between reason and madness in the book, “Almost all the scientists populating the book are mad, their desire to understand, to grasp the core of things invariably wedded to an uncontrollable mania; even their scrupulously observed reason, their mode of logic elevated to religion, is framed as a form of madness.”

In the book, when a character asks von Neumann how he can be so cavalier about the consequences of the hydrogen bomb, von Neumann casually answers, “I’m thinking about something much more important than bombs, my dear. I’m thinking about computers.”

What’s at the bottom of the jar?

In a chapter narrated by Eugene Wigner, von Neumann and he end up discussing the Pandora’s box. Von Neumann asks Wigner if he knew what had remained inside the box after she had opened it and let out all the evils into the world.

Von Neumann says, “Right there, at the bottom of the jar—because it was a large urn or a jar, you know, not a box at all—right there, waiting quietly and obediently was Elpis, which most people like to regard as the daimona of hope and counterpart to Moros, the spirit of doom, but to me, a better and more precise translation of her name and of her nature would be our concept of expectation. Because we don’t know what comes after evil, do we? And sometimes the deadliest things, those that hold enough power to destroy us, can become, given time, the instruments of our salvation.”

When Wigner asks him why the gods would let out all the hurts, pains, illnesses, and inquiries to roam free while keeping hope trapped behind the lid of the jar, von Neumann winks and says, “…because they know things that we can never know.”

“That is exactly how I feel about him, and the reason why I have always resisted condemning Janis, or judging him too harshly, because I believe that a mind like his—one of inexorable logic—must have made him understand and accept many things that most of us do not even want to acknowledge, and cannot begin to comprehend.”—Eugene Wigner in The MANIAC

Labatut suggests the way to live in a world that doesn’t make sense is to hold the contradictions and paradoxes in our hands. We can have all the power in the world, all the reason and logic, and yet suffer like a madman. Melancholy often accompanies deep thought and we simply have to make peace with the human condition.

Giving humanity some hope from the madness of genius, Tom McCarthy writes, “In a wonderfully counterintuitive volte-face, though, Labatut has Morgenstern end his MAD deliberations by pointing out that humans are not perfect poker players. They are irrational, a fact that, while instigating ‘the ungovernable chaos that we see all around us,’ is also a ‘mercy’ that saves us, ‘a strange angel that protects us from the mad dreams of reason.’”

The writer behind The MANIAC

“It doesn’t matter how successful you become in South America,” Benjamín Labatut tells Adam Dalva, “you’re never going to live off literature. You go into it knowing that it’s a failed enterprise.”

Benjamín Labatut was born in the Netherlands and lived there until he was two years old. He went back to Chile and lived there until he was eight, then moved back to the Netherlands until he was about 15- or 16-years-old. His family moved a lot and he moved with them, growing up halfway between Chile and the Netherlands, speaking English. “So I’m not really Chilean; definitely not Dutch,” he says in the same interview.

Labatut is interested in science, in singularities, and in mad scientists. According to Sam Leith, “The characters to whom Labatut is attracted are those who pursued these discoveries, at the cost of their peace of mind and often their sanity.”

Even though Labatut conveys complex ideas of science and mathematics in his books, he himself, in his own words, “cannot teach my 12-year-old daughter simple mathematics.” To him, a writer’s mind works with sympathy, not with understanding.

He talks about a “deep personal crisis” he went through at the age of 30, something that “damaged a part of my brain that can enjoy the games of narrative.” In his interview with Sam Leith, he elaborates, “The people I admire the most in every field have this wondrous ability to let their unconscious bleed into what they do. I really think that the highest form of intelligence is possession from outside. I knew that I didn’t have that, so I did a bunch of very irresponsible things trying to kickstart that…It was catastrophic for me in many ways, but it also helped pave a personal path to writing.”

Labatut was a “nothing journalist” for almost two decades, refused promotions to focus on writing, had lunch by himself every day for 17 years, not accepting any invitations, eventually realizing that literature, for him, required a sort of certain “controlled psychosis.”

Most novels are boring. What then, interests him in fiction?

When it comes to fiction and novels, Labatut isn’t a fan of most fiction. There are few writers whose work Labatut enjoys: Pascal Quignard, Roberto Calasso, W.G. Sebald, and Eliot Weinberger. To him, fiction is not about character or voice or self-expression. What then, interests him in fiction?

“What fascinates me most is things that remain mysterious, things that are unsolved,” he says to Sam Leith. “I’m interested in ideas. I think so much of writing doesn’t have to do with ideas. It has to do with, you know, the vicissitudes of our character. Those things bore me to death. I haven’t been able to read a novel in more than a decade, probably.”

“In every single chapter of that part,” he elaborates on The MANIAC’s structure, “I am thinking that there’s an idea I have to get across. I’m trying to get people to be turned on by the crisis in the foundation of mathematics. I’m trying to get people to feel the horror and beauty of the first nuclear approach.”

They’re not important to me!

He’s not interested in capturing a voice: “They’re not important to me! If you’re in London, you go out there, you listen to a bunch of voices around you. Just record them and imitate them! That’s not difficult! I don’t understand why there’s all this crazy, ’Oh, we captured this.’ What is difficult is for any of those characters to say something interesting!”

In an email to Adam Dalva, Labatut wrote, "The only thing I find striking about myself (and I’m not at all proud of this, but I have to admit to it openly) is how many books I simply detest.”

On the topic of autofiction, Labatut said, “I think Bolaño said it best, right? If you’re a mass murderer, or, like, a detective in Mexico City, if you run guns with Rambo, then please, please go ahead and autofiction. If you are the world’s best-paid sex worker, then autofiction.”

“Wasn’t it great back when a writer said ‘I’ and you knew they were lying?”—Benjamín Labatut

“But, but…voice, character, feelings, love, friendship, career—haven’t these been the basic stuff of fiction since its 19th-century heyday?” Sam Leith fought back.

Finally, Labatut conceded, “If the writing is great, it doesn’t matter…OK. I’m just not that good of a writer—so I have to write about interesting things. If I was a prose writer, if I was a stylist, sure: I’d tell them who I had sex with and what I had for breakfast. But because I have never considered myself to be that good, I have to write about the most profound and confounding things out there.”

“The best compliment I’ve gotten so far is people telling me, 'Your book gave me a panic attack.’”—Benjamín Labatut in Sam Leith’s profile.

A dying poet who taught Labatut to write

Labatut is quite a mysterious person himself, making sure to keep his profile low. He lives in Chile and has written a few books but most of his previous work is in Spanish and can be quite difficult to find. When Adam Dalva went out in search of Labatut’s earlier books, he found it almost impossible to find his first two books. When Ruth Franklin tried to Google Labatut, she found sparse personal information, a few interviews, and some references for the book but not much else.

The intriguing figures Labatut writes about are also present in his own life, one of whom played a big part in his writing journey—teaching Labatut to write.

When Labatut started writing, his friends sent him to an “old man, a dying poet,” Samir Nazal. He tells the story to Adam Dalva, “I walked into his apartment, and he had a long unkempt beard and was covered in cigarette burns…when he died, he’d never published a word. He had these containers with everything he had written. They were in Tupperware because it rained in his apartment. And I see him in dreams. I see him in hallucinations. Without the old man, I don’t think I would’ve ever written.”

Fact and fiction

On Labatut’s fiction—one where fact and fiction are interspersed—Ruth Franklin asked: “If fiction and fact are indistinguishable in any meaningful way, how are we to find language for those things we know to be true?”

She wondered if it is responsible for a fiction writer, or a writer of history, to pay so little attention to the line between the two. A central idea in Labatut’s fiction is, as Adam Kirsch puts it, “the moral corruption at the core of modern science.”

Is there a moral corruption in the blurry boundary Labatut draws between fact and fiction?

“If we cannot grasp the past or the present (not to mention the future) with any degree of clarity,” Ruth Franklin writes, “then fiction becomes as plausible as history as a method for describing the actions and events of people’s lives.”

“Fiction, as much as physics, is the domain of the multiverse.”—Ruth Franklin in The New Yorker.

Who should we hear?

In his interview with Brain Greene, Labatut is asked about a similar dilemma, "In your book, should we hear Eugene Wigner as saying that or should I hear Benjamín Labatut saying that?”

Labatut responds (edited for clarity): “Well both because they’re mixed, because reality is mixed. I mean, I understand again our need to separate things out is important, but I am a writer of fiction so I don’t need to explain myself in that way because I say very openly and I say it all the time. I write fiction but the problem is that it’s like 95% non-fiction right? But just that 5%…something that I think a lot about is that we never ever interact with reality without putting extra layers of meaning onto it. A chair is never just a chair. Or no matter what I say to you, no matter what my meaning might be intended to be, of course, you’re going to filter it through your entire experience. That’s one of the frailties of the human experience…Nietzsche had this wonderful sense that if you wanted to get at the truth first you had to cover the truth and that’s what books do. You put a veil on things so that you can see them again and science is sort of ripping off the masks.”

In an interview with the Louisiana Channel, Labatut talks about fiction, “Anything that comes out of a writer is fiction. In non-fiction, they are really kind of naïve. Fiction is something that is not appreciated for what it is. It is not the making up of a story; it doesn't have to do with imagination. Fiction is a tool, it is a human tool we developed to give reality a human shape to understand what is presented to us, and that goes on at all levels; it is part of perception. There is a large part of fiction in perception itself; it is not just stories. It goes on all the time; we just don't notice that it is going on.”

Labatut is fascinated by singularities, the things that lie outside the regular order. “One of the things that I get angry about is this modern depreciation of the word genius. As if everybody were the same and it is not like that at all: One of the great things about being human is how different we are. And there are these outliers, men and women, that really seem to come from another world. They suffer for it too. Because it is very dangerous to suddenly discover something new about ourselves, going a step beyond.”

Labatut tries to find himself in others, in books and papers and “shitty blog posts.” He wants to write about things you cannot write about, somehow “disease creeps into everything” he writes.

“How can you get something bigger than yourself to come through? You have to become porous and let the world come through you,” he says.

Ruth Franklin wonders about the obsession with obsession when thinking about Labatut’s “deep personal crisis” he faced when he was 30. “…Labatut’s cautionary tale of great minds unhinged by staring into the abyss may, like Goya’s etching, have a second interpretation that mirrors the more obvious one. Can it be that contemplating such questions is as dangerous as not contemplating them?”

But Labatut wants people to remain focused on his work rather than his personal life, as he tells Adam Dalva, “The less they know the better.” Then adding, a flash of glee in his eyes maybe, “And I’m such an interesting person. You have no idea.”

Move 37 and the Hand of God

“We are a species haunted by itself.”—Benjamín Labatut

In an interview with the Louisiana Channel, Labatut says, “We have to think about God more than we do. Not believe in God but think about God. Gods in general, not just that one. Belief is the death of thought.”

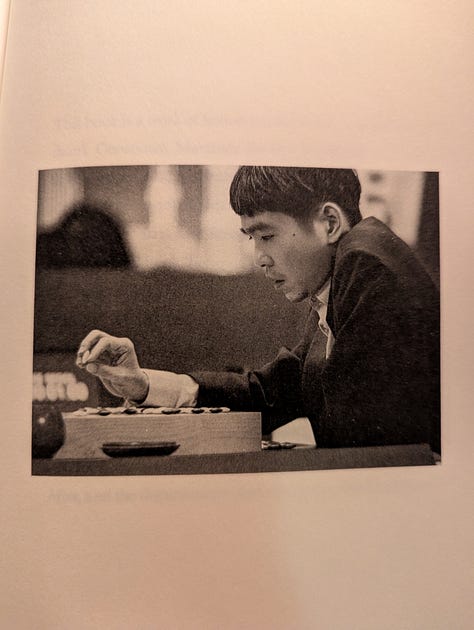

The third part in Labatut’s The MANIAC tells the story of DeepMind’s AlphaGo AI system beating the world’s top Go player in 2016, solving a computational problem that most people believed was still decades away. It brings the story of geniuses like Demis Hassabis and Lee Sedol and pits the human genius against the genius of machines, the same machines that von Neumann envisioned decades ago.

In 2016, as DeepMind’s AlphaGo competed against the world Go champion Lee Sedol, it made a move that sent shockwaves through the world of Go—a move that made no sense, a move that no Go player would ever make or had ever made in 3000 years of Go’s documented history. The move came to be known as Move 37.

Lee Sedol was playing a 5-match competition against AlphaGo and had already lost the first game to the AI system. Even though Sedol had lost, the general consensus was that AlphaGo had gotten lucky and Sedol hadn’t played his signature offense style of Go. But when AlphaGo played Move 37, it changed things; it changed the belief that AI can’t be creative and that it can only spit out what it has seen in its training data. With Move 37, AlphaGo crossed that line. It was making a creative move that made no sense to anyone, not even the 9-Dan Go champion of the world. In that one move, it was almost as if AI had defeated all of humanity. Perhaps we had reached the next step in evolution.

In The MANIAC, Labatut writes, “Technology, after all, is a human excretion, and should not be considered as something Other. It is a part of us, just like the web is part of the spider.”

Sedol lost the third game as well. There were no ground-shattering moves by any of the two players. AlphaGo had won as if it was playing against an amateur.

To me, it is the game 4 that is most interesting. After 3 hours into the game, Sedol made a move that no one understood. The commentators thought it was a stupid move. Perhaps Sedol had really lost it.

But then, something fascinating happened. In the control room, AlphaGo’s probability of winning the game dropped from 70% to 20%. It started making moves that felt random—like a deer caught in the headlights. With each move, AlphaGo made its position worse. After a few moves, it slowly dawned on the commentators and professionals watching the match that Sedol had achieved something amazing.

Sedol had played his own version of Move 37, in a way. He had found a chink in AlphaGo’s armor and attacked it right where it would hurt the most. It was a gambit but a considered one. AlphaGo lost that game. AI lost a game, after a long battle, to human genius and creativity.

Even though Sedol lost the 5th game, it didn’t matter. Lee Sedol had shown that even when AI systems become unbeatable they remain vulnerable. There is hope for the future. He proved that humans are more than just training data and an algorithm, that the best of humanity can still stun the system, and can still win if only it perseveres. The move that Sedol had played? It was called, aptly, the Hand of God.

“I heard people were shouting from joy when it was clear that AlphaGo had lost the game. I think it’s clear why: People felt helplessness and fear. It seemed we humans are so weak and fragile. And this victory meant we could still hold our own. As time goes on, it’ll probably very difficult to beat AI. But winning this one time…it felt like it was enough. One time was enough.”—from The MANIAC

A symbiotic co-evolutionary loop

Both AlphaGo’s Move 37 and Lee Sedol’s Hand of God demonstrate that AI and humanity are in a symbiotic co-evolutionary loop. As AI systems get better and unlock more of our understanding of the workings of the human brain and become better at tasks than humans, humans can learn and evolve from competing with these systems, the same way the AI systems learn and improve from their experience with humans: co-evolutionary reinforcement learning.

“Facing each other, Lee and the computer had managed to stray beyond the limits of Go, casting a new and terrible beauty, a logic more powerful than reason that will send ripples far and wide.”

“When future historians look back at our time and try to pin down the first glimmer of a true artificial intelligence, they may well find it in a single move during the second game between Lee Sedol and AlphaGo,” writes Labatut about Move 37.

A Promethean bargain

We live on a giant rock filled with molten lava floating in the middle of nothingness. In the 1940s, the American Prometheus, along with some of the greatest minds on the planet, gave us the tools to destroy ourselves: the Atomic Bomb. A few years later, some of those same geniuses, with the help of John Von Neumann’s MANIAC, gave us the Hydrogen Bomb: a bomb 100x more powerful than the one dropped on Hiroshima.

Yet here we all are, still alive and well, ignoring the MAD world we live in. We’re living through similar times today and the search for AGI is perhaps our version of the same Promethean bargain. Few geniuses, still in search of what the likes of Turing and von Neumann had started, playing with fire. All we mortals can do is hope they don’t burn the whole world down like that test in Los Alamos could have.

“You insist that there is something a machine cannot do. If you tell me precisely what it is a machine cannot do, then I can always make a machine which will do just that.”—John von Neumann

In his interview with Sam Leith, Labatut talks about language and mathematics: “When you have a mathematical system that can run language, you have the two most powerful things we have developed as a species working together: mathematics and language. I think that we are absolutely on the verge of something, if not past the verge. I think that the first AI catastrophe, because of the way things are going, massive corporations racing to the bottom, is probably inevitable…It’s been, what—since quantum mechanics and modern relativity—100 years? One hundred years after Christ was nailed on a cross, you start to get the Gospels. That’s where we are.”

For all the progress in AI, Labatut does think—rightfully so—that names like DALL-E and ChatGPT are “such shit names…which makes me sad. These people don’t have what von Neumann had, that is, the breadth of culture. They’re not reading the Vedas like Oppenheimer. It’s a world that’s tiktok-ing its way to annihilation.”

In his review, Adam Kirsch writes about the tragic arc of The MANIAC: “Enhrenfest dreaded the emergence of an inhuman intelligence, von Neumann made that emergence possible, and now Lee sees it taking place in front of him.”

For progress, there is no cure

A few years after that game with AlphaGo, when Lee Sedol retired from the game of Go, he said, “I thought I was the best, or at least one of the best. But then artificial intelligence put the final nail in my coffin. It is simply unbeatable. In that situation, it doesn’t matter how much you try. I don’t see the point…AlphaGo did not beat me, it crushed me…Even if I become the best that the world has ever seen, there is an entity that cannot be defeated.”

To Sedol, Go was not just a game, it was a way of understanding the world in all of its puzzling complexities and unfathomable intricacies: “If someone was somehow capable of fully understanding Go, and by that I mean not just the positions of the stones and the way they relate to one another but the hidden, almost imperceptible patterns that lie beneath its ever-changing formations, I believe it would be the same as peering into the mind of God.”

But there is a chink in the armor. The Hand of God showed us that. Are we really at the cusp of something world-altering? Are we really tiktok-ing our way to annihilation with the machines that we are obsessed with creating? Are the geniuses aware of the danger of their inventions or are they so enamored by the thrill of scientific discovery that they simply do not care?

“For progress, there is no cure,” says Labatut, channeling something von Neumann had once said, “but remember it is us who do these things. So we can find ways to use technology. Technology and science are indifferent. It is up to humans.”

In Labatut’s book, von Neumann on his deathbed gave his parting vision for AI and consciousness:

Before he became unresponsive and refused to speak even to his family or friends, von Neumann was asked what it would take for a computer, or some other mechanical entity, to begin to think and behave like a human being.

He took a very long time before answering, in a voice that was no louder than a whisper.

He said that it would have to grow, not be built.

He said that it would have to understand language, to read, to write, to speak.

And he said that it would have to play, like a child.

The hope under the lid of the jar

In an interview with the Louisiana Channel, Labatut talks about beauty, “Beauty is the most important thing there is. I think the truth is completely secondary. Life and beauty are completely intertwined, and we don’t realize it. We don’t understand that it is something that was here before us. We are just interacting with some of its versions. It is not just in the flowers but also beneath the ground, in the dirt; it is everywhere. It is the universe being in love with itself.”

In the madness of human ingenuity, we once created the atom bomb and decimated entire cities. Who is to say we won’t be capable of doing the same—something worse—with the inventions that we are pursuing? “In the long term,” Labatut suggests, “it may be humanity that has to submit.”

Perhaps Labatut is right. Maybe we will all, in the end, lead ourselves to our own destruction, machines we built willing us into submission. Or maybe there is still some hope? Maybe there is more to us humans than simply logic and reason, madness and irrationality.

After his final defeat against AlphaGo and years before he retired, Lee Sedol shared some words of hope and optimism: “I don’t necessarily think that AlphaGo is superior to me. I believe that there is still more that human beings can do against artificial intelligence. I feel regret, because there is more that I could have shown. Go is a game that you enjoy, whether you are an amateur or a professional. Enjoyment is the essence of Go. And AlphaGo is very strong, but it cannot know that essence. My defeat is not mankind’s defeat. I think that these games clearly showed my own weaknesses, not humanity’s weakness.”

We are living in the world of John von Neumann. As Adam Kirsch writes, “When science is inhumane, humanity has the right to take its revenge.” If only Pandora could open her jar once again and save men from the fire.

References

This essay would not be possible without the brilliant work of others mentioned below.

The Smartest Man Who Ever Lived, by Adam Kirsch in The Atlantic. (Link to article)

‘People say my book gave them a panic attack’: When We Cease to Understand the World author Benjamín Labatut, by Sam Leith in The Guardian (Link to article)

Benjamín Labatut Will Not Be Profiled, by Adam Dalva in Literary Hub (Link to article)

A Cautionary Tale About Science Raises Uncomfortable Questions About Fiction, by Ruth Franklin in The New Yorker (Link to article)

The Miracle and Madness of Science That Changed the World, by Tom McCarthy in The New York Times (Link to article)

A Brief History of the Mind in the Machine: John von Neumann, the Inception of AI, and How the Limits of Logic Can Liberate Us, by Maria Popova in The Marginalian (Link to article)

Louisiana Channel interview #1 (Link to YouTube)

Louisiana Channel interview #2 (Link to YouTube)

The World's Smartest Mind: Exploring the Extremes of Thought with Benjamin Labatut, interviewed by Brian Greene for the World Science Festival (Link to YouTube)

Natalie Portman’s interview for her book club (Link to Instagram)

Pandora’s Box: The Myth Behind the Popular Idiom, by Rittika Dhar in History Cooperative (Link to article)

Writer’s note: If you liked this essay, please share and/or click the like button. In this algorithmic world of von Neumann, that helps a lot :)

I find the comments around AlphaGo fascinating. Especially the part about one side of the game being that you just have fun with it. A machine doesn't have this right now (maybe one day who knows...). It's a super interesting thought on what makes us human and what we should prioritize because AI can never do this for us (eg. Have fun).